A Look at My Work

The Chinese are attempting to build a new empire using

infrastructure development. The goal is simple:

Make economies reliant on China.

Likely the most ambitious infrastructure project in history, China plans to invest between four and eight trillion dollars into developments across Europe, Asia, and Africa. Well over a trillion dollars has already been invested into this plan through roads, railways, and pipelines. This is only the beginning, as China has expressed plans for or is already underway on construction projects in over 68 countries, which are responsible for approximately 30 percent of global GDP.

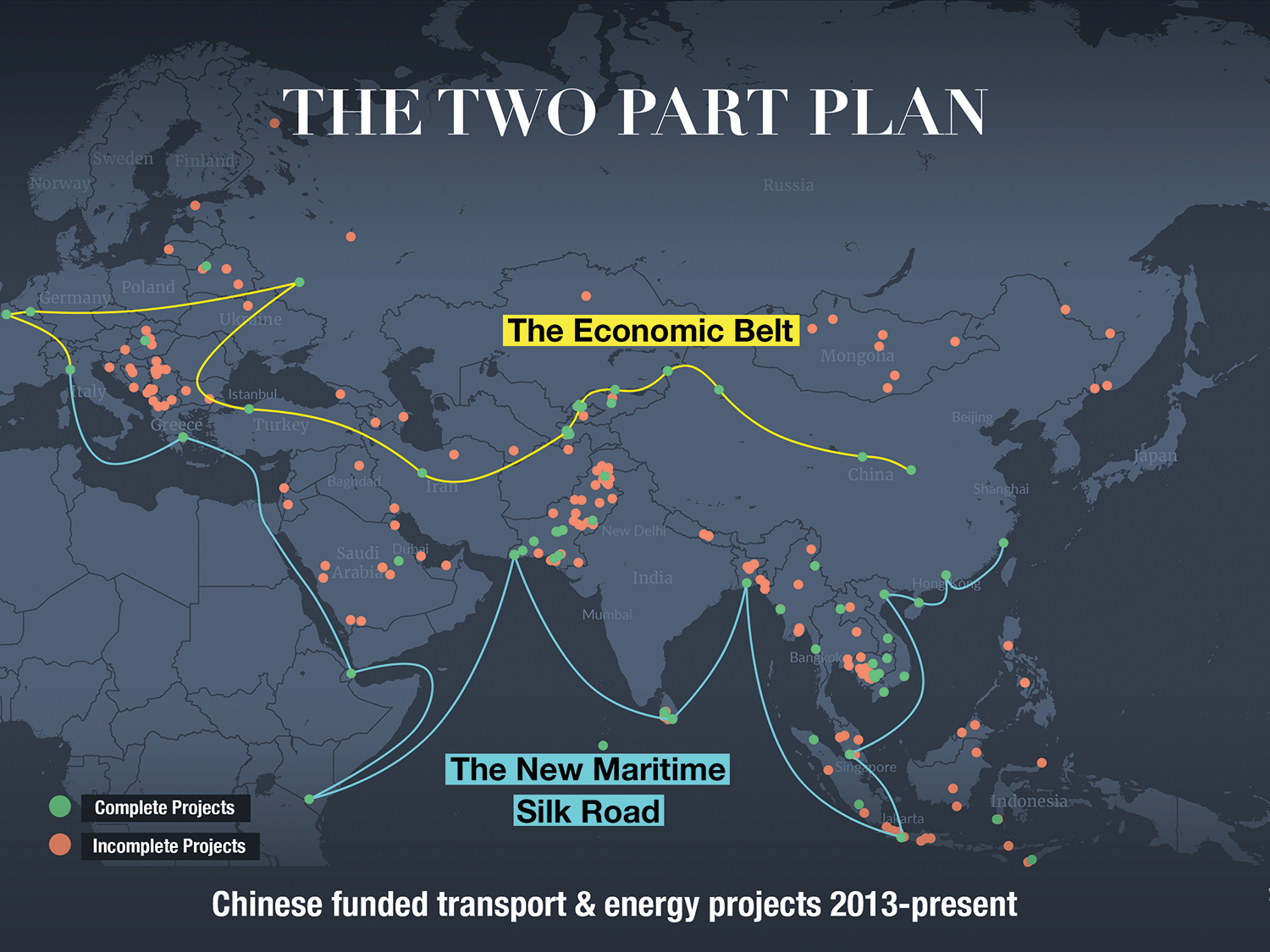

The ‘belt’ is a series of land projects.

The new silk ‘road‘ is a chain of sea ports.

These key locations connect global trade.

President Xi Jinping has publicly stated his goal to “build an economic belt” as well as to construct a “new maritime silk road.” This so-called ‘belt’ consists of overland routes (roads, railways, pipelines, bridges, etc.) which can be subdivided into six connecting corridors that control the flow of trade between Asia and Europe. The ‘road’ involves a chain of seaports connecting the South China Sea to the world. These developments come with many benefits, such as cutting transit times between China and London in half. But they are not without their costs.

These new developments come at a cost to those who take part. By offering to build and finance infrastructure to poorer nations, China gains invaluable leverage.

These projects are primarily targeted at developing economies in need of economic growth. China agrees to construct much needed infrastructure under the condition that only Chinese banks are used to finance the project and only Chinese construction companies are used for building it. Many of these projects cost as much as the countries’ entire GDP, leaving them with crippling debt. In Pakistan, for example, China is constructing a new port, highway, and railway network. Collectively these developments costs $62 billion, or 20 percent of Pakistan’s total GDP.

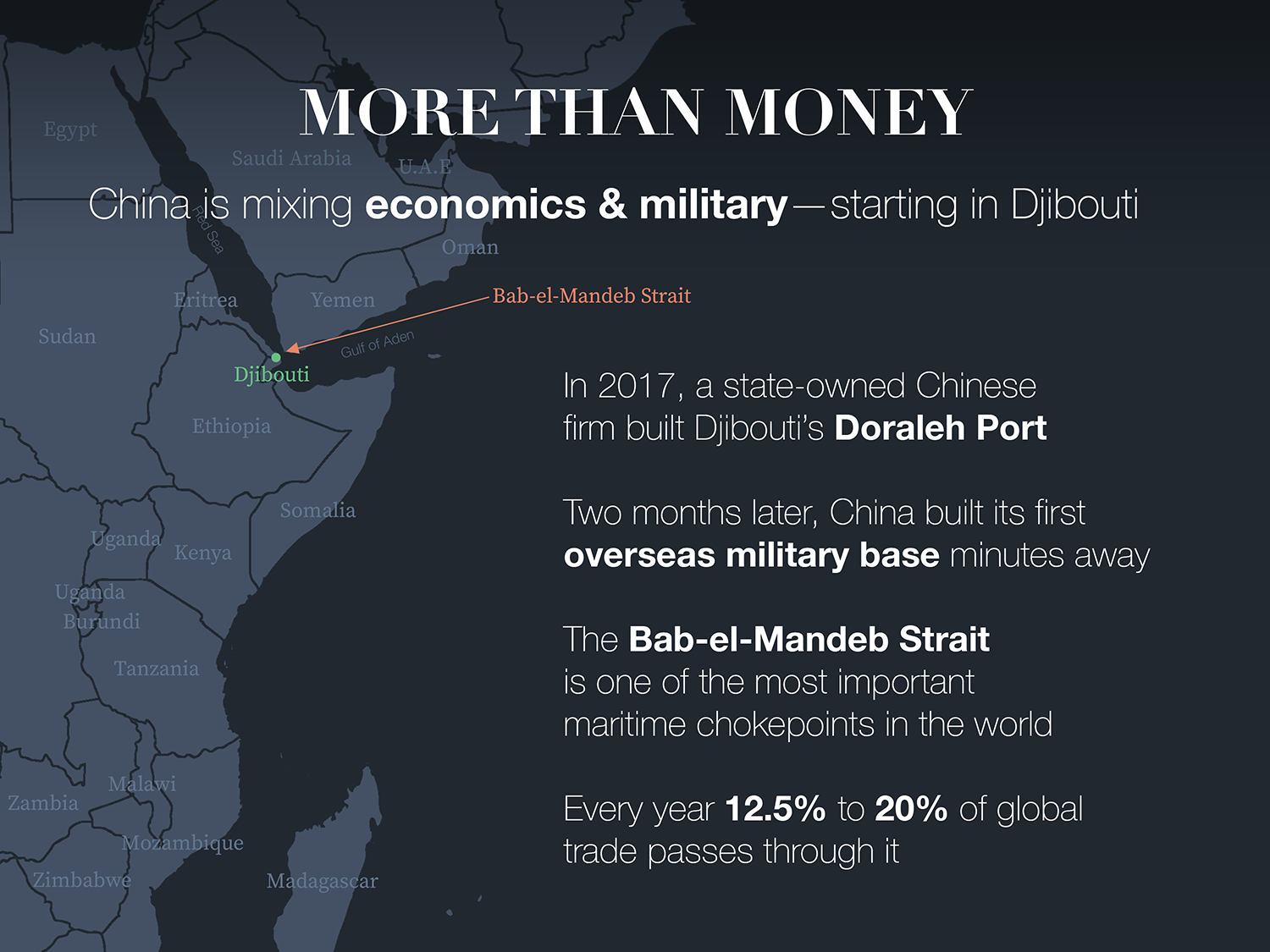

Inevitable loan defaults result in the Chinese owning developments in other nations. This new land can be used for strategic military and economic strongholds.

Because the costs of these infrastructure projects are so exorbitantly high, developing nations ultimately fail to repay China. This gives China the power to negotiate new terms. In multiple instances China has transferred foreign debt to equity by pushing for extended leases on the infrastructure they have built. This has led to Chinese ownership of ports, bridges, railways, and highways across the world, giving China control over key global trade routes. In Pakistan, for example, China now has a 40-year lease on the port it built in Gwadar. In Sri Lanka, it now has a 99-year lease on the port it built in Hambantota. China's goals don’t stop at trade, either. In Djibouti, China has built its first foreign military base only 8 miles from a US military base. This location is key for its strategy proximity to the Bab-el-Mandeb strait, a maritime chokepoint.

Until action is taken by other world powers to prevent predatory lending practices by China, nations around the world will be in debt to them.

The United Nations and International Monetary Fund have both condemned China’s predatory lending practices, lack of transparency, and high interest rates. But these condemnations are useless against an economic superpower offering billions of dollars of investment to nations that are desperate for growth. To prevent China from gaining ownership of strategic trade and military locations, other world powers must work with developing nations to offer alternative loan options. With diplomacy failing to yield effective results and military intervention off the table, competing with China by offering a safer source of investment is the only foreseeable strategy.